Genesis 2:15

The Lord God took the man and put him in the garden of Eden to work it and keep it.

Colossians 3:23-24

Whatever your task, put yourselves into it, as done for the Lord and not for your masters, 24 since you know that from the Lord you will receive the inheritance as your reward; you serve the Lord Christ.

Today is Labor Day, when Americans pause and reflect on the meaning of work and honor working people. Let us acknowledge that that many people who are looking for employment, perhaps within our own families. Let us keep them in our prayers and send them job leads if we find any. And those of us who are working or, in retirement, enjoying the fruits of labor past, let us be thankful for it and be willing to help others now.

On Labor Day we acknowledge the importance of work. We spend more time working or perhaps looking for work than anything else we do. It would pay, therefore, to take a look at what Christian faith can tell us about work and its place in our lives.

I remember when people used to utter the words, “Protestant work ethic” as a shorthand way of talking about certain habits of work that were seen as the foundation upon which America’s material prosperity was built. The Protestant work ethic was a philosophy born from the Protestant Reformation of the early 1500s. Until then the labor or ordinary people was thought to lack either divine sanction or divine opportunity. Instead, what ordinary working people did was seen as necessary but spiritually deficient. Ordinary people were thought incapable of attaining anything better than a "secondary grade of piety." The "perfect form of the Christian life" was "holy and permanently separate from the common customary life of man." devoted "to the service of God alone."

Reformation theology turned that around. The Protestant reformers insisted that the ordinary occupations of men and women should be understood as honoring God just as well as the monastic or priestly life. One’s “calling” in life came to be understood as any honorable occupation that a person understood was willed by God for him or her, so anyone, not just clergy, could be called by God to a lifetime of Christian service in different ways.

This Protestant work ethic says we are to be honest, hardworking, reliable, sober, mindful of the future, appropriate in our relationships and successful. We add that those things enable a Christian to give glory to God.

In Ephesians 4:28, Paul said that people should work with their own hands at what is good, in order that to have something to share with one who has need. Honorable work is honest work, honestly performed. The Protestant work ethic extends past that simple rule, though. There is an object to work for Christian people: to build up the Kingdom of God for the greater benefit of all the people of God. In the final analysis, all our labor is to be for the glory of God by the way it enables us to be about the ongoing work of Christ in the world.

I think we must not separate the dignity of work from human dignity. I read recently that in Japan almost no one ever gets fired from a job. We probably might say that is because the work ethic and skill levels among Japanese workers are so strong there. But that is not the reason. The reason hardly anyone ever gets fired is because by law terminated employees must be given very substantial separation payments and benefits. But if an employee simply quits, there is no such requirement.

So a common practice in Japan is for nonperforming workers to be assigned extremely menial, unimportant duties that, the company hopes, will so dispirit the worker that he will finally quit in despair rather than go nuts.

If you think that can never happen here, think again. In New York City it is so difficult to fire certain kinds of city employees that the ones identified for termination wind up being reassigned to completely empty offices or even utility closets, devoid of any responsibilities at all, while continuing to collect full salary and benefits, which cost the city $22 million one year recently.

This is not what God intended from the beginning. In the beginning, God gave Adam work to do in the Garden. This means that Adam in his vocation was a partner with God in accomplishing God's intentions for the created order. It’s true that things went sour later. Indeed, the first murder recorded in the Bible, when Cain killed his brother Abel, was in part over the way Cain perceived the nature of Abel’s work and vocation.

Paul wrote in Colossians 3, “Whatever you do, work heartily, as for the Lord and not for mortals, knowing that from the Lord you will receive the inheritance as your reward. You are serving the Lord Christ.”

Paul points toward a unity in our lives that brings even our jobs under the lordship of Christ. In other words, he is describing striving for a restoration of our work to the kind that Adam enjoyed. We are not to spend our lives idly, but in divine vocation. And even though there is an earthly imperative to pay bills and hopefully enjoy life without financial worry, we also are called to remember what Jesus said: we cannot serve both God and money.

But we can serve God by making money while remembering that no earthly treasure lasts and that Jesus also told us, “Do not store up for yourselves treasures on earth,” where it can be lost, corrupted or stolen. “Store up for yourselves treasures in heaven,” for God's care never ends. Where our treasure is, that’s where our hearts follow.

Jesus is talking about more than money. He means the whole of life and what we do with our time. And that is the necessity of seeking a divine vocation because there is a difference between a job and a vocation. A job is what we do to earn a living. A vocation is what gives our lives meaning and purpose. A job is always related, usually closely, to worldly affairs. A vocation transcends the world even though it is carried out in the world.

For truly fortunate persons their job and their vocation can be united or closely related. When I was a candidate in ministry, I decided to ask a number of serving pastors what was the single most important thing about pastoral service to each of them. I asked twelve pastors independently, over a period of a few months and all twelve gave me exactly the same answer: “I know that I am doing with my life what God wants me to do with it.”

That is precisely how I feel, too. I consider myself profoundly blessed to have my vocation and my work united into a singularity. I never awake in the morning wondering what my life is about.

I am not saying, by the way, that I do this job well or effectively. It is to say that in my heart I know I have found that place that Methodist author Robert Robert Kohler wrote about: “There are different kinds of voices calling you to different kinds of work, and the problem is to find out which” voice is the call of God rather than the voice of self-interest, cultural values or something else.

One’s vocation is the life-work that a man or woman is called to by God. It is always a call to ministry of some kind. One’s vocation may or may not be the way that you make your living. I have known some persons who thought their income-producing job was merely a crutch that propped up their true mission in life, their vocation.

Kohler wrote, “The kind of work that God usually calls you to do is the kinds of work that you need most to do and that the world most needs to have done.” Your vocation is not necessarily what takes the most time in your daily lives. It is what gives the rest of your life focus and meaning. Frederick Buechner wrote, “The place God calls you to is the place where your deep gladness and the world’s deep hunger meet.” God calls each Christian to use his or her gifts in the world. One test of identifying your calling is to discern whether it satisfies your hunger to be about the work of Christ in the world. If someone doesn’t have a hunger to be about the work of Christ in the world, then their chances of discovering their true vocation are slim. Yet unless persons discern their vocation, they waste their time, money and in fact their very lives.

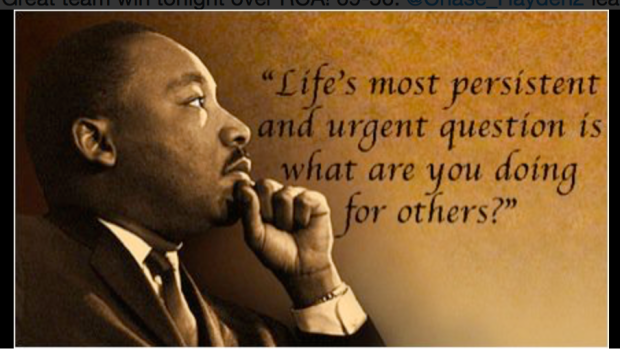

In 1967, Martin Luther King preached on, “The Three Dimensions of a Complete Life,” in which he said,

… we must discover what we are called to do. And once we discover it we should set out to do it with all of the strength and all of the power that we have in our systems. And after we’ve discovered what God called us to do, after we’ve discovered our life’s work, we should set out to do that work so well that the living, the dead, or the unborn couldn’t do it any better. Now this does not mean that everybody will do the so-called big, recognized things of life. Very few people will rise to the heights of genius in the arts and the sciences; very few collectively will rise to certain professions. … But we must see the dignity of all labor.

Perhaps some of you feel that your work is a calling, enabling you to honor and serve God in ways you wouldn’t be able to do otherwise. If so, be glad! Christian faith sanctifies every honorable occupation. There isn’t any difference between the secular and the sacred, not really. Jesus was a preacher for three years but a carpenter for at least twenty. That sanctifies work. All of life is God’s, so let us strive to make sure that all we do glorifies God.

Here is Dr. King's complete sermon: