Just War Theory (JWT henceforth) forms the basis of modern international law regarding the causes, conduct, and conclusion of warfare. JWT is not a modern concept, however. It has sprung over many centuries of thought in the Christian traditions to resolve the tensions between the teaching of Christ and the realities of national affairs in a fallen world. For example:

The principal influence on JWT were Saint Augustine, AD 354-430, and St. Thomas Aquinas of the 13th century. Of the two, Aquinas remains the more influential and all work on JWT since him builds on his work.

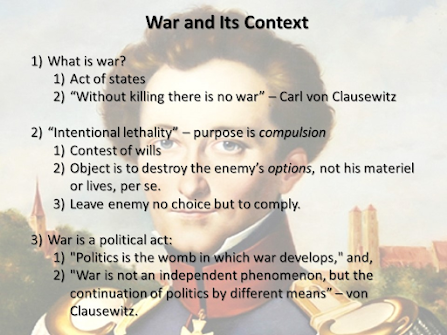

But what is war? The question seems self-evident, but modern Conventions such as The Hague and Geneva Conventions are careful to define. For centuries, war has been understood to be an

act of nation-states, not of combat between non-state combatants, no matter how well armed and organized. Understand, however, that armed conflict between a nation state and a non-state combatant does qualify as war under the Conventions and other relevant treaties.

War is an act of deliberate destruction of an enemy's lives or physical assets. Absent "intentional lethality," there is no war regardless of what armed forces may otherwise do. Historically, however, the purpose of those operations has not simply to kill, but to compel submission by the enemy. As the US Army's World War 2 Gen. George S. Patton said, "Battles are won by frightening the enemy. You frighten the enemy by inflicting death and wounds."

Europe's most celebrated theoretician of war is Prussian Gen. Carl von Clausewitz, 1780-1831, whose book, On War, is still studied around the world. One of his central tenets is that, "Politics is the womb in which war develops," and therefore, war is "the continuation of politics by different means.”

Today's conventions clearly recognize that principle.

In theorizing about war, these are the underlying visions of warfare that are used, usually more than one is used.

As you can see, a nation's leaders may use moral principles to decide that employing the armed forces is justified under the various Conventions and the leaders' own national principles. But they may also see that while war is morally justified, it would be unwise and would likely have unacceptable outcomes.

And that leads to what are the bases, or templates, for which war might be made? I will let my slides speak for themselves:

Just War Theory JWT is a holistic view of war with a focus on attaining justice, limiting suffering, and encompassing all three of:

- The cause of war

- The conduct of war

- The termination and aftermath of war

So, let's look at the basic details:

Just War Theory, along with international conventions and accords, forbid wars of conquest or aggression. The basic principle is that a nation may justly go to war to defend against aggression or to protect such aggression against third parties. However, Europe's history, culminating in the 30 Years War of the early 1600s, led to rejecting protection of third parties as an excuse to go to war. The Peace of Westphalia established national, geographic boundaries as the demarcation of nations (warring of parties), not language, tribal identity, or ethnicity. And the Peace deliberately set the internal affairs of a nation as immune from interference, especially war, by other states.

This has formed a foundation for "governance" (if one may use that word) for war ever since, and is reflected strongly in the United Nations charter. The UN charter does explicitly allow for international alliances outside the UN that may establish war making for defensive purposes, with NATO being a primary example.

Just War Theory holds as a matter of principle that making war therefore must be undertaken to establish a more just peace than pertained prior to the conflict. And the war may not itself be of greater evil than that it seeks to prevent.

That war may not justly be waged absent reasonable prospect of success is important. It relates directly to the tenets of just conduct of war, and especially the greatly misunderstood principle of proportionality, about which more later.

The Principle of Proper Authority

Just War Theory mandates that nations may go to war only with proper authority to do so. There is no international agreement on what that may be as a universal standard. The UN Charter permits specific kinds of war without UN consultation, but requires UN Security Council approval for other wars. (President Truman, for example, gained UNSC approval for the Korean War.)

The UN Charter also recognizes that nations make security arrangements and treaties outside the UN structure. The most famous example is Article 5 of the NATO Charter, which requires every NATO member nation to respond militarily if any NATO member is attacked and Article 5 is invoked.

However, the only authority that can declare the United States is at war is the US Congress, not the UN. Treaties do not overwhelm the US Constitution. The UN cannot make American war legal or illegal, but it can make it legitimate in eyes of world.

The US Constitution distinguishes between declaring war, which can be done only by Congress, and making war, which is the purview of the executive. As then-Senator

Joe Biden accurately explained in 2001, the Congress has declared war when the Congress thinks it has. Hence, he said, an Authorization for the Use of Military Force meets Constitutional muster as a declaration of war.

I'm the guy that drafted the Use of Force proposal that we passed. It was in conflict between the President and the House. I was the guy who finally drafted what we did pass. Under the Constitution, there is simply no distinction ... between a formal declaration of war, and an authorization of use of force. There is none for Constitutional purposes. None whatsoever.

Constitutional lawyers over many decades have held that varying kinds of enabling acts, such as monetary appropriations for military action, have also amounted to Constitutional satisfaction and, at least, consent of the Congress to action ordered by the president, in whom the Constitution grants authority to conduct warfare.

Just Conduct of War

Let me begin by reiterating that warfare is intentional lethality and destruction. Just conduct of war means that there must be limits to both. And that is where the principle of proportionality comes in.

The doctrine of proportionality is simply stated that the means of conducting the war must be proportionate to the goal for which the war is waged. Another way of looking at it is that while the just ends desired do not justify any means to attain them, they absolutely justify some means. The tenet of proportionality, then, is to assess what the justified means are, then employ those means and not the unjustified ones.

The centering question of the doctrine of proportionality is deciding the violence necessary to achieve the war's objectives while not using excessive violence to do so. To employ too little violence is as disproportionate as to employ too much. It is unjust to wage war ineffectively even for a just cause.

Hence, proportionality means that one cannot use more force than necessary, but must use all the force that is necessary. It is critical to understand that proportionality does not mean, and never has meant, anything like a tit-for-tat response.

In this, as in most of the just conduct tenets, huge gray areas of uncertainty abide. The combatants must do the best they can.

The doctrine of Discrimination of violence means that weapons may not be employed with little or no regard to the nature of the target. Specifically, non-combatants may not be deliberately targeted and in fact, warring parties must use all achievable means to avoid it. But as warfare of the past 100-plus years has showed, it is permissible to bomb enemy factories even though factory workers are not members of the military.

However, an international standard called Common Article 3 governs combat between state and non-state combatants. Its states that civilians' presence at a location does not automatically make that location off limits from attack. As Human Rights Watch explained during 2006's Hezbollah war,

It, too, can be targeted if it makes an “effective” contribution to the enemy’s military activities and its destruction, capture or neutralization offers a “definite military advantage” to the attacking side in the circumstances ruling at the time.

Other Categories

- There are Hague Protocols on chemical and biological weapons. In this, United States policy since at least the 1960s has been in compliance. It is that the US will not use bioweapons, period, and will not be the first to use chemical weapons, but retains the right to respond likewise against an enemy's use of them. (As for nukes, US policy has not changed since they were invented: We have atomic weapons, and if you do not want us to use them, then do not attack us. Other nuclear-armed nations have basically the same stance.)

- Use of civilians as hostages or “human shields” is prohibited.

- Hospitals, other categories (such as houses of worship) may not be attacked.

- No “false flagging,” such as marking combatant vehicles with the insignia of the International Red Cross.

- Honorable surrender is defined, required to be honored. Pretense of surrender is prohibited for any reason.

- Militarization of protected structure removes its protection. A hospital, for example, may not be bombed, but if a combatant places anti-aircraft weapons atop it, it may legally be leveled without warning.

- The Conventions specify permissible treatment of POWs and refugees, including prohibitions of torture and other actions.

- Retribution actions are permitted, but very narrowly. For example, if a combatant nation executes 20 POWs because two of them had attempted escape, the those soldiers' nation may execute in retribution POWs that it holds, but only up to a point.

The Conventions also specify occupying power obligations and define the distinction between lawful and unlawful combatants. Unlawful combatants are not afforded all the protections of lawful combatants.

And the Conventions define and require the responsibility of moral action and accountability for all sides. That is, a warring nation is required to bring to discipline any member of its armed forces who commits a war crime.

Just Ending of War

Here, there are three guiding principles:

- Enduring peace

- Restraint of the victor

- Reconciliation among warring parties

What is the future of JWT, especially in its relation to international accords? I close with a link to an article by Jeff McMahan, professor of philosophy at Rutgers University and author of

The Ethics of Killing: Problems at the Margins of Life and

Killing in War. Click here: "

Rethinking the ‘Just War,’ Part 1" (part 2 is linked at the end of that article).